Loowit Trail

It was a terrible mistake and I shouldn't have done this trail. Sheer luck and generosity of other hikers are the only two reasons I'm not a hero of an article about local Search and Rescue trying to airlift a hiker from Mt. St. Helens.

This hike report is long overdue. I’ve taken a whole week off work to do this hike and apparently it took me over a week to come up with a sensible story about it. This is a long one, so bear with me. Or don’t.

The idea to hike the Loowit Trail came to me way back, probably, around 2013, when my family and I visited Johnston Ridge Observatory.

I learned that there was a hiking trail right at the bottom of the breached side of the volcano, and I had this trail in mind ever since.

Mt. Loowit (St. Helens)

Throughout this post, sometimes I will refer to Mt. St. Helens by its native name, Loowit (Lawetlat’la, Loowit or Louwala-Clough to be precise). For centuries, the mountain had its name, but colonizers in their infinite arrogance decided to give it a new name. In 1792 Commander George Vancouver named this landmark after his friend British diplomat Alleyne Fitzherbert, 1st Baron St Helens.

Mt. Loowit is the youngest volcano in the Cascades. It is located on the indigenous lands of Cowlitz and Klickitat native people (now part of Yakama Nation). The slopes of the mountain above the treeline are a Traditional Cultural Property of Cowlitz and Yakama tribal groups. For thousands of years, the mountain has been a central place in the culture and mythology of the tribes, where resources were gathered and young people were sent to test themselves.

Although I only ventured above the “treeline” once or twice along the Loowit trail, I can clearly see why this incredible place is at the center of indigenous cultures. I encourage you to take a look at some of the legends collected and passed down through generations.

May 18, 1980

Prior to May 18, 1980, Mt. St. Helens was a beautiful cone-shaped peak, sometimes referred to as Mt. Fuji of the Pacific Northwest. It all changed early on that day. There are a few fantastic documentaries about the infamous eruption and the subsequent largest landslide in recorded history.

Ever since the eruption, Mt. St. Helens fascinated scientists, hikers, photographers, writers and became a preserved natural treasure.

The trail

Of course, there’s a hiking trail around the volcano, it’s PNW, what did you expect?! :)

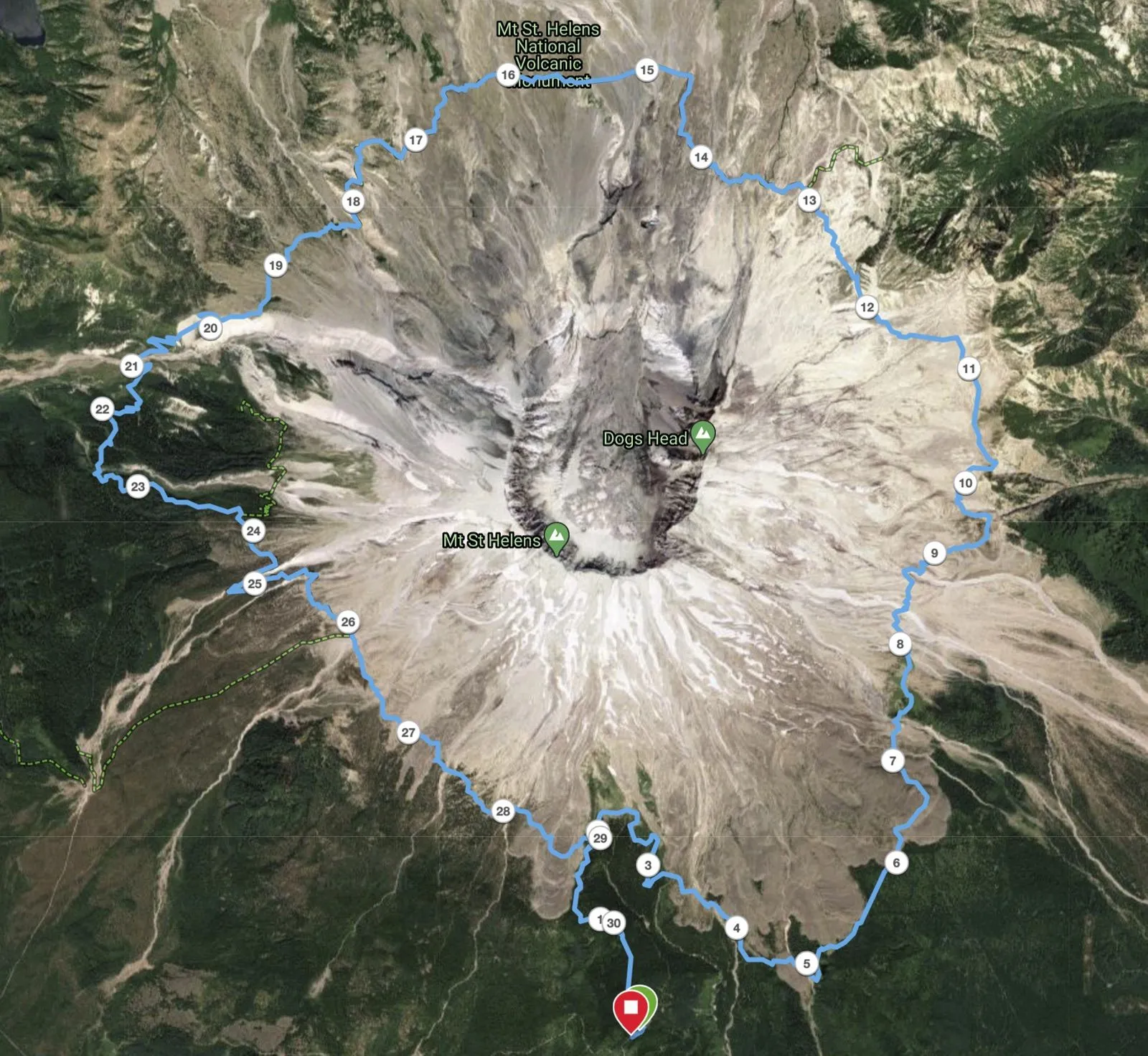

The Loowit Trail circles the mountain at about 4400 ft of elevation, sometimes dipping as low as 2900 ft and soaring to over 4800 ft. Its length depends a lot on the approach, but generally, it’s considered to be between 30 and 35 miles, with a total elevation gain of around 9000 ft.

The trail is considered to be Difficult to Expert level, and for a good reason: it throws every possible terrain and challenge at you, all the time! I don’t know what I was thinking when I decided that I should totally hike it: I’m not in great physical shape and my backpacking experience prior to this hike was limited to 2-nighters. Anyway, I was set on hiking it during my time off, and when I’m set on an adventure, nothing can stop me (except for a broken leg, evidently)

Preparation

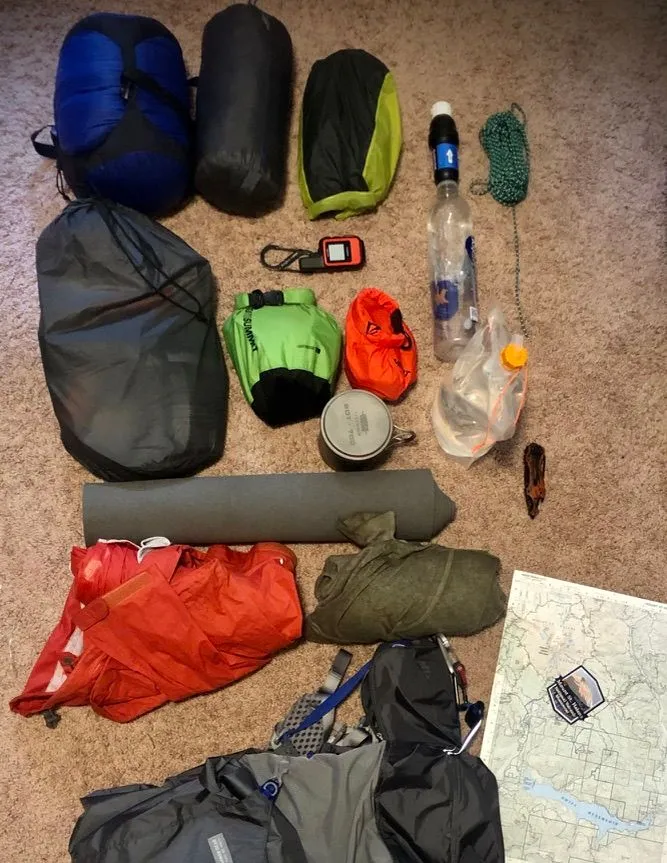

For this hike, I went all-in on ultralight gear. Ultralight tent, ultralight quilt, ultralight sleeping pad, ultralight backpack, the list goes on. I trimmed my base weight to about 12 pounds, which is quite fascinating if you ask me. I also had 2 65 oz bottles for water and another 2-liter water bag.

So on the gear front, I was well-prepared and ready to go. Some things that I’ve taken with me I hadn’t used a lot or even at all, but those were minor and inconsequential.

I was not as prepared physically as I thought I was but will get to it.

On Sunday, I arrived at Climbers Bivouac, set up my tent, quickly drove to Portland to pay my respects to the folks protesting in front of the Injustice Center. I got back to the camp after dark and went straight to sleep. Tomorrow was going to be a long day.

Day one

I got up pretty late — most climbers were long gone. The weather was perfect for me: low overcast, fairly chilly, and quiet.

The first segment of the hike is the approach to the Loowit Trail. To get to the trail from the camp, you need to hike up Ptarmigan trail for about two miles and something like 700 ft of elevation, until you hit an intersection with Loowit trail. There, I took a right turn and proceeded counter-clockwise.

The trail was fairly light for the first few miles. It mostly went downhill, and the climbing segments were fairly light. The views were already quite impressive, especially if you consider that there’s a looming volcano behind the clouds!

This first part of the trail, approximately between Climbers to Windy Pass has quite a few water sources, and it gave me a false impression that water is not going to be a problem. Yes, this water was silty and muddy, but it’s water so who cares, right?!

I topped up my water containers here at the Chocolate falls and hit my first challenging segment: Worm Flows. This is basically a giant lava boulder field you need to cross. The trail is non-existent, and you hop from boulder to boulder navigating to the next white stake in the distance.

The day was going towards sunset at this point, so I pushed forward to hit my Day One target (about 7 miles) and set up camp for the night before dark.

And there you have it. Day one was in the books, I felt pretty good about my progress and the fact that I hit my first target. There were some wild animals sniffing around the tent all night, but nothing interesting happened, and I didn’t find any interesting footprints in the morning.

Day two

When you backpack for days, at some point it’s easy to sync with the sun. You wake up around sunrise and normally settle down for the night right after sunset. At least that’s my experience.

Day two began early: I had about 6-8 miles to hike through pretty rugged terrain and under full sun and clear skies. My goal was to push all the way to Windy Pass — the edge of the Restricted zone in front of the Breach — the part of the mountain that got destroyed during the eruption.

As mentioned before, the terrain on this stretch of the trail is pretty rough. Looking back, it’s not that rough, especially compared to some later segments.

The views were breathtaking. I paused every now and again just to stare in the distance, taking it in as much as I can.

Rugged boulder fields turned into a huge stretch of huckleberry fields. Quite literally, you’re making your way on a narrow trail slicing an endless huckleberry field! The berries were ripe, juicy and so very tasty!

I was getting pretty tired. All these uphills, boulders, lack of shade began to take tall. I refilled my water at Muddy River, and realized that I’m probably not going to make it to my target area before sunset.

I pushed forward for as long as I could. The problem was that since I was tired, hot, and pushing, I drank a lot of water. And I was running out fairly quickly. I decided that I’ll go until I find a water source and will break camp somewhere nearby.

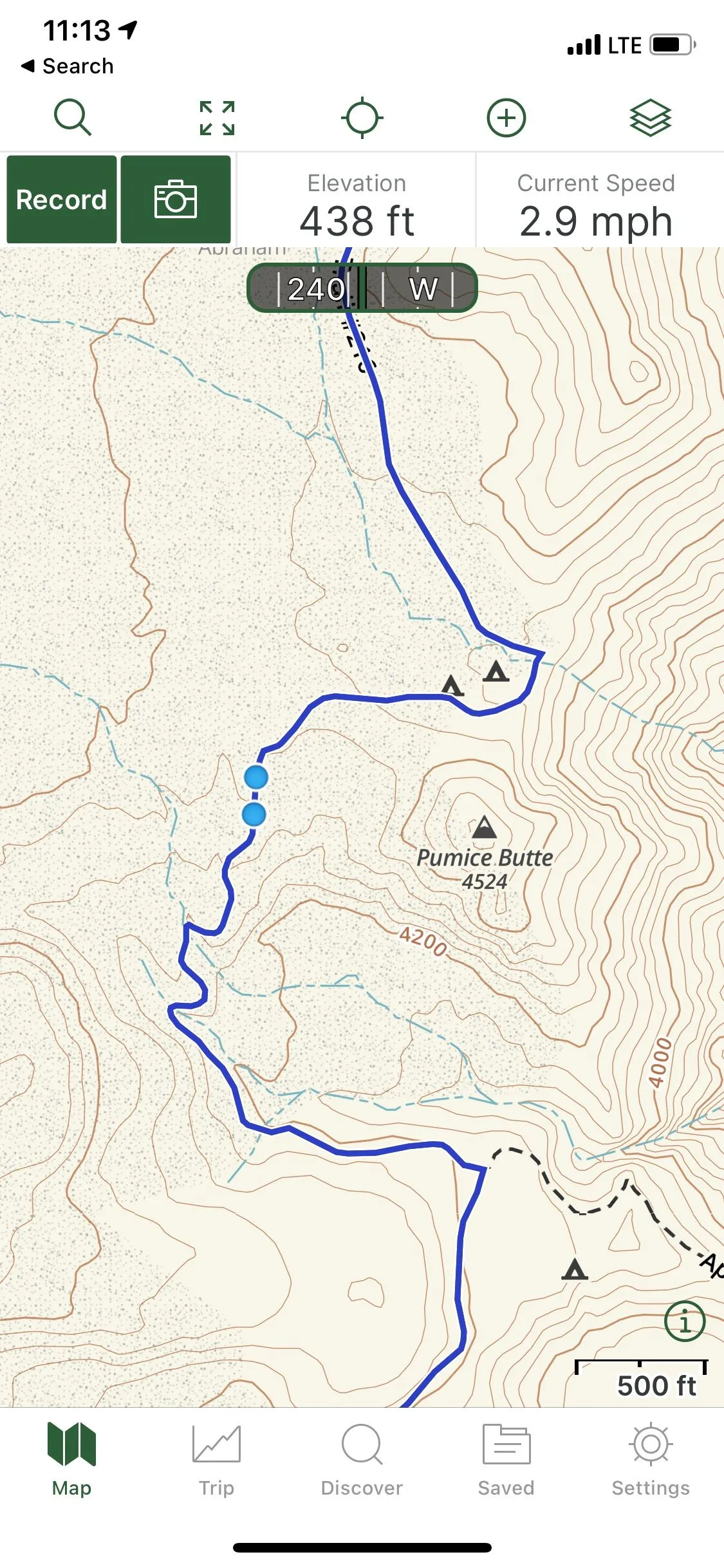

I use Gaia GPS as my primary navigation app, and I truly love it. Aside from providing 100s of map layers (including cell coverage, air quality, and more), it has some unique data I relied on in this trip: campsites.

I was lucky enough to chat with a fellow hiker who let me know that the creek that looks to be running by the campsite here, in fact, changed and is now running quite a bit to the West. This spot became my new goal for the day.

I arrived at the campsite right before sunset, set up a tent, enjoyed the view for a bit, and went to sleep.

Day three

When this is what you wake up to, the day just can’t be bad!

I think now is a good time to mention a few things that very clearly went wrong by this point:

- I was running out of water much faster than I could find water sources.

- I somehow punctured my inflatable sleeping pad and despite my repair efforts, it was deflating almost completely within 1-2 hours. My back wasn’t happy about this, and sleep quality got pretty low.

- The food I brought with me was either dehydrated or too sweet for me to hold. By this point in time, I haven’t eaten much in the past 2 days, yet it didn’t bother me yet

- I was running ~3 miles behind schedule. With a Restricted Zone looming ahead — you must cross it’s ~9 miles in one go, no camping allowed — I will have to cover these 3 miles and 9 miles of the Restricted zone today in order to camp legally. 12 miles is ok on easier trails, but by this time I realized that 12 miles in one day on this trail is probably beyond my abilities.

With all this in mind, I embarked on this most exciting part of the trail — the one that crosses the Breach and pumice fields left in front of the mountain by the 1980 blast and subsequent landslide.

The first few miles from my camp to Windy Pass were a breeze. The mostly flat prairie-like trail all the way to the pass. I enjoyed my walk a lot, and was wondering for a while whether I could’ve made it the day before. I probably could have pushed for a few more miles, break camp after dark beside the Windy Pass and shave these extra miles off of my Restricted Zone day.

Going over the pass look intimidating at first, but was in fact fairly easy. The trail there goes along the hillside and is not very stable and has a few really sketchy spots, but overall it was easier than I expected.

The following few miles go over the side of the mountain slowly introducing the Breach — the side of the volcano destroyed by the blast in 1980. For me, this was the most exciting part of the journey. Walking on top of many feet of fairly new volcanic ash, seeing the destruction side of the volcano myself, and traversing many canyons, streams, and erosion areas while seeing the mountain at a very unusual angle.

It’s been 40+ years since the eruption, yet the mountain is still settling in. Constant rock fall noise, steam, and ash floating in the air, ever-changing streams and riverbeds — it will likely take hundreds of years for all this stuff to calm down. Geologically speaking, 40 years is nothing, a blink of an eye, so from the volcano’s perspective, it just erupted moments ago and the process of healing hasn’t even started yet. Biologically, though, even in the blast zone, life is everywhere. From grass and weeds to all sorts of shrubs and sub-alpine flowers and native trees, it’s all here. Chipmunks, coyotes, birds of every color, elk, and deer, it’s all here.

To say that this is an active and dangerous volcano would be an understatement. In the past 30 days, there were close to a dozen earthquakes under Mt St Helens, and every year there periods of swarm earthquakes: dozens of magnitude 1-3 shakes that happen within days and weeks. Something is still going on down there, and at any point, the mountain can start erupting again (the same way it happened twice in 2006 and then in 2008).

This is the heart of the blast zone. Behind me is the gaping wound left by the eruption. You can’t hear rocks falling, but you can see clouds of ash they send up in the air.

By this point, I’m exhausted. A few miles back, I hit an oasis: a little stream, ice-cold and absolutely clear, surrounded by some trees and bushes. I refilled all my water containers, relaxed in the shade for a bit, and pushed forward through the blast zone.

My goal for the day was to get to the South Fork Toutle River — the next water source and the place where the restricted zone ends and camping is allowed again.

By the time I left the breach area, I was at the end of my rope: I was tired, I practically ran out of water, and I still had about 4 miles ahead of me to get to Toutle River. There was no way I’d make it there, and it was time to admit it and plan accordingly.

I decided to push as far as I humanly can, again. With canyons turning deeper and deeper, and hiking mostly uphill at this point, this “as far as humanly possible” turned out to be about 2 miles or so. I found a spot (still in the restricted area) and pitched my tent — there was no way I’d cross this canyon today. I fell asleep almost immediately.

By this time, I had exactly two sips of water left and 2 miles to hike up and down to the next water source. I was in trouble.

Day four

This was one of those days when you think: “Ok, how can I quit this now?” And the answer is, basically, you can’t. At this point, there’s no exit from the trail that would take you to people faster. There’s no way around the upcoming Toutle Drop (I’ll get to it in a minute). There’s no quitting, only pushing ahead and hoping you can make it, which at this point was not a sure thing.

I had my sip of water for breakfast and hit the trail. Since I haven’t eaten much and started to get fairly dehydrated, I got to the point of being slightly delirious. I had to take breaks every few hundred yards — taking my pack off, spreading my sleeping pad, and just laying down for a few minutes. The next 2 miles were the longest two miles in my life.

Luckily, I met another hiker, who was generous enough to share half a bottle of water with me. I’ve taken a picture of him on his phone in return, and was incredibly grateful for the water and some tips on what awaits me ahead.

Ahead was the Toutle Drop. I don’t think it’s an official name of this feature, but every hiker I’ve met referred to it like this.

Right there, at the very bottom of this by far the deepest canyon on the trail, there is a tiny stream. It’s Toutle River, and in fact, it’s not so tiny, it’s just very far below.

The Drop is a sharp descent over a slope of the canyon. You go down on loose pomace and volcanic ash. One sloppy or unsteady step, and you will lose your footing and tumble hundreds of feet down to the bottom of the canyon.

By the time I got to the final ~30 feet rope-climb down to the river, I was set on spending the rest of my day right there, by the water. All the water I can drink! Flowing, roaring, splashing! Sweet, sweet unlimited water!

I spent about 3 hours by the river. There was not a spot of shade, so I covered myself with my sleeping mat, and just laid there for hours, drifting asleep, hot and tired. Every now and again, I’d go and refill my water bottle, drink it all, doze off for a bit and repeat. I even ate half of one of my sweet food items: even if I can’t hold it and vomit it right away, at least I’d have enough water to recover quickly. It went fairly well, and provided some necessary calories and a slight energy boost.

In front of me was a daunting uphill stretch of over 2000 ft of elevation. Also, there was an intersection where I could attempt to exit the trail: I could hike lower, take a trail that goes parallel to Loowit trail, and pop out at a road leading to the Climbers Bivouac. By my estimations, this path was about a mile longer but offered fewer elevation changes. The biggest downside was that the final mile or so was a roughly 1000 ft ascent, overall elevation gain would be approximately the same as at Loowit trail, and this other trail was unlikely to have any hiker traffic in case I pass out. At this stage of my hike, passing out became a real concern, and I had to keep it in mind.

I refilled my water containers for the last time: there will be no water for the next 8+ miles. Basically, there will be no water all the way to the trailhead parking. Or so I thought. I took another nap at the campground just above the river, and made an executive decision to attempt to exit the trail by taking this other trail I described above. There will still be a chance to return back to the Loowit trail later without losing anything.

I hiked for a couple of miles through the forest and set up camp right over a river beside a sturdy bridge over Sheep Canyon. It was a relief to find more water: it meant that I could have all the water I want for breakfast and refill once more before the final push to the parking lot. I was very much set on finishing tomorrow, no matter what.

Day five

I woke up early and was in a good mood. I was still weak, exhausted, and ached all over from sleeping on a deflated sleeping pad, but it was my last day on the trail. The plan was this: I hike to the trailhead, get into my car, drive to Vancouver, WA, eat Wendy’s Double Baconator and gulp a large diet Vanilla Ginger Ale, spend the night at a nice hotel, take a shower and do the laundry, and drive home the next morning.

Motivation, unfortunately, is not enough for pushing through 8 miles of very challenging mountain terrain. I’ve barely eaten in 5 days, poorly hydrated, sore all over; the sun is mercilessly shining, deep canyons with rope climbing and another set of lava boulder fields lie ahead.

Honestly, I remember very little about this day. I remember taking long breaks every few hundred yards. Just laying down for a few minutes (hours?), rationing water, and dreaming about Vanilla Ginger Ale.

I set myself a miles countdown: 2 miles before the parking lot, I’d hit the approach trail — 2 miles of 100% downhill. So I subtracted these 2 miles from whatever milage I had left. Roughly speaking, I just needed to push through about 6 miles of the trail to get to this final trail intersection and then just descent to the parking lot.

…Of course, I ran out of water about 3 miles before my target intersection.

…At sunset, I met two hikers who shared some water with me, and strongly suggested I spend the night in a little patch of trees right ahead of me: attempting to cross another boulder field at night in my condition concerned them gravely, and I concurred. I crossed a patch of boulders, entered a tree patch, spotted a tiny opening besides the trail, and set there for the night. Words “Cowboy camping” popped into my clouded mind, and given that was pretty much unable to think straight or do much, I decided to give it a shot. Cowboy camping is, basically, camping without a tent. You just unroll your sleeping mat, lay down, and sleep under the stars. Not in a nice hotel after a double baconator as planned, but right there in the bushes, with one of my dry sacks as a pillow and with a buff covering my face and ears from insects.

In all honesty, it wasn’t too bad. And the night sky was absolutely, incredibly covered with stars with Milky Way visible so clearly, I didn’t know it was even possible to see it like this. As for the insects — my biggest concern — aside from a few random ants crossing my legs a few times, no one bothered me.

Finale

Well, this Saturday had to be my last day. With just about 2-3 miles to the parking lot trail and 2 miles of downhill, I had to make it there today. I woke up at about 6 o’clock, and by then I knew what to expect. In a few minutes, runners will start passing by. About an hour or so later, I’ll meet the first hikers. In about 2 hours, I’ll meet the majority of people who started the trail today. By this time, all of it was clear and very predictable. I got up stuffed my dew-soaked quilt into the pack and started my final hike.

I ran out of water pretty quickly. I didn’t have much to begin with, probably 4 or 5 sips, and the adventures of the week took their toll — I had to drink. I met a few people in the next mile or so, mostly runners, and you don’t ask runners for water: they are on the clock, and they have smaller water reserves. I was lucky, again, to meet a fellow hiker who looked at me after I asked for a sip of water and just refilled my whole bottle. He explained that he’s been in a similar situation more than once, and it was time for him to pay it forward. I was so grateful! A full bottle of water! I drank half of it within minutes :)

Crossing the last boulder field, dried out Swift creek, and — finally — here’s the intersection with a trail going downhill to the parking lot! I made it!

About an hour later, I put my backpack in the trunk of my car and left Climbers Bivouac. Alive, hungry, dehydrated, sore, and aching all over, dirty but happy that I made it.

Lessons Learned

- Dehydrated food is nice, but it’s useless without water. The same goes for sweet food. Also, always test any new trail food before taking it with you. There’s a chance you are not compatible with it.

- Fewer moving parts next time: no inflatable sleeping pad — no problem. No stove, no problem. You get the idea.

- Water planning and management are key. Especially if you drink a lot. Consider trails with water readily available instead of hiking trails known for their long dry stretches.

- Cowboy camping is ok. Not a fan, but it’s totally an option in an open space. Wouldn’t do it in a forest, though.

- If you’re set on a trail that you think maybe more challenging than what you can handle, consider your exit strategy. More than once I thought about exiting the trail. And every time I convinced myself that I shouldn’t. If I had a clear strategy of when, where, why, and how I could exit, I’d probably cut the trip short but also wouldn’t suffer as much :)

- Have your location beacon ready. More than once I was this close to pushing the SOS button and just giving up. I passed out a few times and had difficulty standing up, and thought that this is it, an SOS situation. Ironically, it gave me a sense of confidence: well, I can always call for help, so let me just try and push a bit further, and if I absolutely cannot move anymore, I’ll do the SOS thing. I never did, of course, but this option was very much on the table.

Now what?

For about 3 days after I got back home, I was recovering from severe dehydration and also eating like crazy. I bought a watermelon, a bunch of grapes, and a ton of other juicy fruit. I drank a lot, and it’s hard to appreciate tap water enough until you have no access to water for days. All things considered, I recovered fairly quickly. But I still haven’t unpacked my backpack.

For about a week after my return home, I was absolutely, 100% done with backpacking forever. Never again will I voluntarily subject myself to this kind of experience! NEVER!

About 2 weeks later, as I finishing this story, I’m thinking about where can I go next? What short, 1-2-night hike is easy enough yet interesting and exciting? And as of the time of this writing, I’ve got a few ideas ;) But to be completely honest, my 2020 backpacking season is probably over. I’m likely to take a few day hikes, an overnight maybe, but that’s about it. Next year, I’ll do this whole Loowit trail again, clockwise this time, earlier in the year when the water is abundant and all creeks are still flowing. With this experience, it’s going to be a breeze and walk in a park! Right? RIGHT?!